Feb. 29th, 2020

Why You Should Eat Your Cactus

Text © Julia Georgallis

Images © L&O

Eating for Adversity

Some people live to eat. But we all, undeniably, eat to live. Odd then that our eating habits currently threaten our very survival - we eat too much and distribute resources in destructive ways, contributing to a declining environment. We may, however, be able to eat our way out of crisis by learning how to steward the land more efficiently.

Unless you have been living on an undiscovered island, you may have heard that subsisting on plants rather than animals is better for the planet. However, I would argue that, given our poor track record, it will not simply be a case of eat-more-vegetables-and-it’ll-be-ok. It is also a matter of which plants do we grow and where do we plant them? Globalisation and industrialised farming mean agricultural conglomerates with complicated technologies at their disposal can bypass climate altogether. Hence, the average westerner no longer eats seasonally, accustomed to bananas on tap and avocados plentiful.

Across the globe, entire landscapes have been altered for cultivation - Spain grows fruit and vegetables on previously arid land, importing soil and employing the use of hydroponics. In Chile, civil unrest bubbles as large avocado farms illegally divert water from small, drought-stricken communities. And in California, oases of thirsty almond trees grow in the desert, with water redirected from the other side of the state. These places are considered ‘bread baskets,’ important to international food chains. Yet, as global temperatures rise, they risk either total or further desertification. Should we grow such highly water-dependent plants on land that doesn’t naturally support them? Do we need to start growing vegetation that is accustomed to hotter climates?

Across the globe, entire landscapes have been altered for cultivation - Spain grows fruit and vegetables on previously arid land, importing soil and employing the use of hydroponics. In Chile, civil unrest bubbles as large avocado farms illegally divert water from small, drought-stricken communities. And in California, oases of thirsty almond trees grow in the desert, with water redirected from the other side of the state. These places are considered ‘bread baskets,’ important to international food chains. Yet, as global temperatures rise, they risk either total or further desertification. Should we grow such highly water-dependent plants on land that doesn’t naturally support them? Do we need to start growing vegetation that is accustomed to hotter climates?

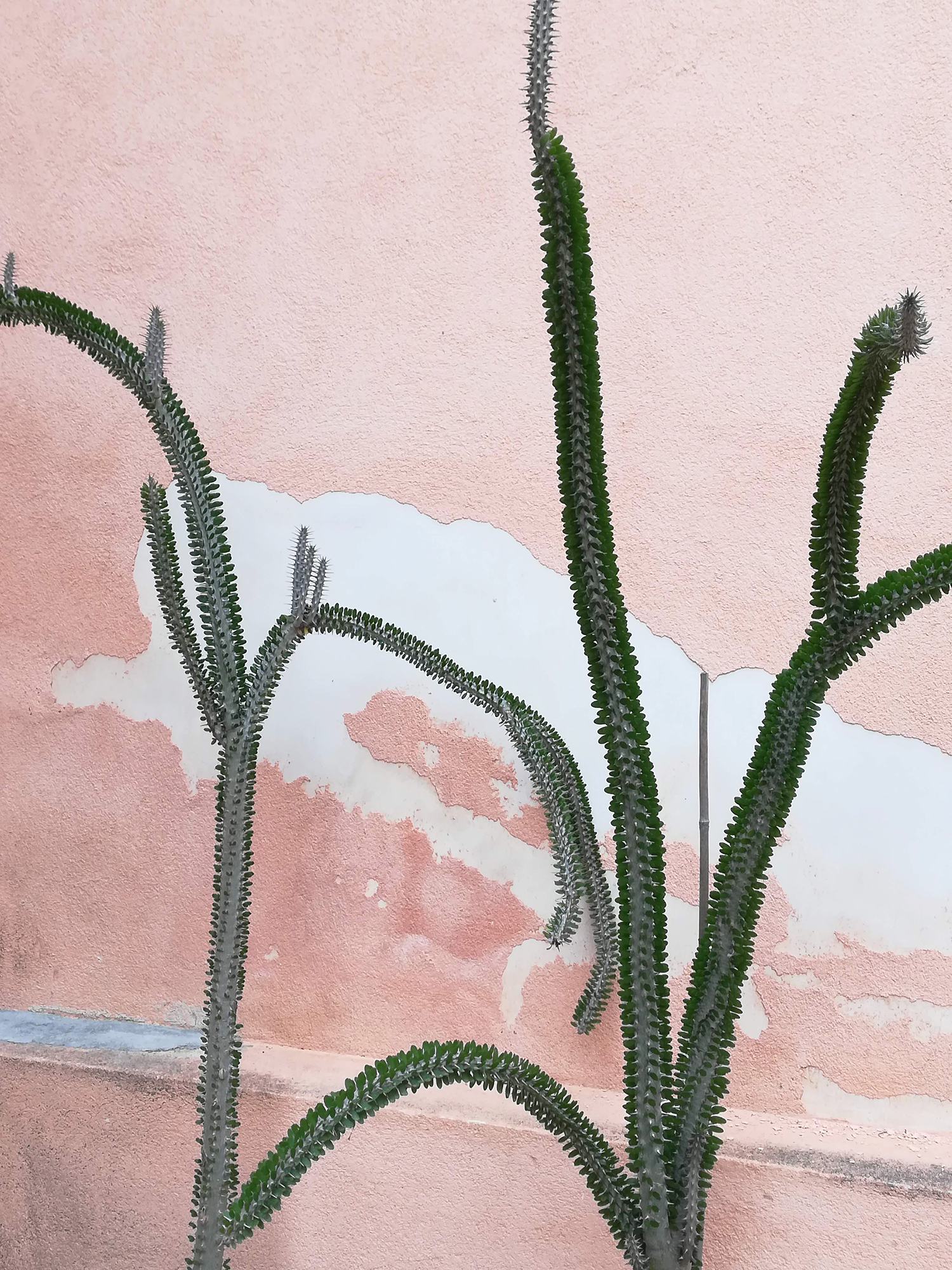

As well as for food, we grow plants because they look pretty, perhaps in an attempt to reconnect ourselves to nature in an increasingly screen-based life. Sales of cacti and succulents, in particular, have increased by 64% between 2012 and 2017. But this too has implications - growing numbers of endangered cacti are stolen from National Parks, and rare succulents now appear on lucrative black markets - take too much out of any eco-system and nature’s scales are tipped.

With scarcer resources, we are asked to live more sustainably but are simultaneously encouraged to consume more, to eat and buy more plants. As we face desertification, is it overly decadent to keep plants simply as ornaments? Could we (and will we one day have to) begin to eat our cactus or succulent? It would be a bit like growing a herb garden, but contrary to needy herbs, cacti and succulents are at home anywhere, no environment too dry, no owner too unloving. Sound painful? It could be if you don’t prepare your barbed banquet properly, but many types have been eaten for centuries and are delicious. We can learn much from these desert-dwelling shrubs.

With scarcer resources, we are asked to live more sustainably but are simultaneously encouraged to consume more, to eat and buy more plants. As we face desertification, is it overly decadent to keep plants simply as ornaments? Could we (and will we one day have to) begin to eat our cactus or succulent? It would be a bit like growing a herb garden, but contrary to needy herbs, cacti and succulents are at home anywhere, no environment too dry, no owner too unloving. Sound painful? It could be if you don’t prepare your barbed banquet properly, but many types have been eaten for centuries and are delicious. We can learn much from these desert-dwelling shrubs.

Though cacti and succulents are generally slow growers, they are enduring and resourceful, unlike sensitive fruit and nut trees. We could plant them on land that has become too dry for other flora and harness their drought resistance to ease some of the tensions we currently place on the planet. Humans are hard-wired to panic at the prospect of sparsity, but cacti and succulents stay calm, steadying themselves with their armoury of spikes, digging deep into the earth, taking only what they need not what they want. We would do well to view them as totems for self-sufficiency and hardiness in the face of an adverse, hot and unstable future…

This piece is the first chapter of a 2-part article written by Julia Georgallis about her research on edible cacti. Read the second part here

This piece is the first chapter of a 2-part article written by Julia Georgallis about her research on edible cacti. Read the second part here

Bibliography

The EAT-Lancet Commission on Food, Planet, Health, ‘Food in the Anthropocene: The Eat-Lancet commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems’ (2019). Date accessed: 1st February 2020

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, ‘Global Warming of 1.5oC’ (2018). Date accessed: 14th November 2018

The Guardian & The Pacific Standard, ‘This Land is Your Land’ (2020). Date accessed: February 14th 2020

About the author

Julia Georgallis is a baker who used to be an industrial designer. She is the author of cookbook, How to eat your Christmas tree and runs micro-bakery, The Bread Companion as well as various other side hustles. Her work revolves around looking at food as a design solution and as an educative, empowering tool. www.juliageorgallis.co.uk / @juliageorgallis