Dec. 4th, 2020

Creole Poietic

Little Stories of Plants in the French West Indies: Between Creation, Resistance and Resilience

Text & illustrations © dach&zephir

This piece is the second chapter of a 2-part article written by French duo dach&zephir about Éloj Kréyol, their ongoing research around the notion of creolisation and the post-colonial landscape of the Antilles islands. Read the first part here

Among the many stories of "creolisation through plants", those of the grenn a maléré, the bwa lélé, the coui and the balé zo are particularly interesting because of the capacity of these plants to become tools of creation, resistance and resilience.

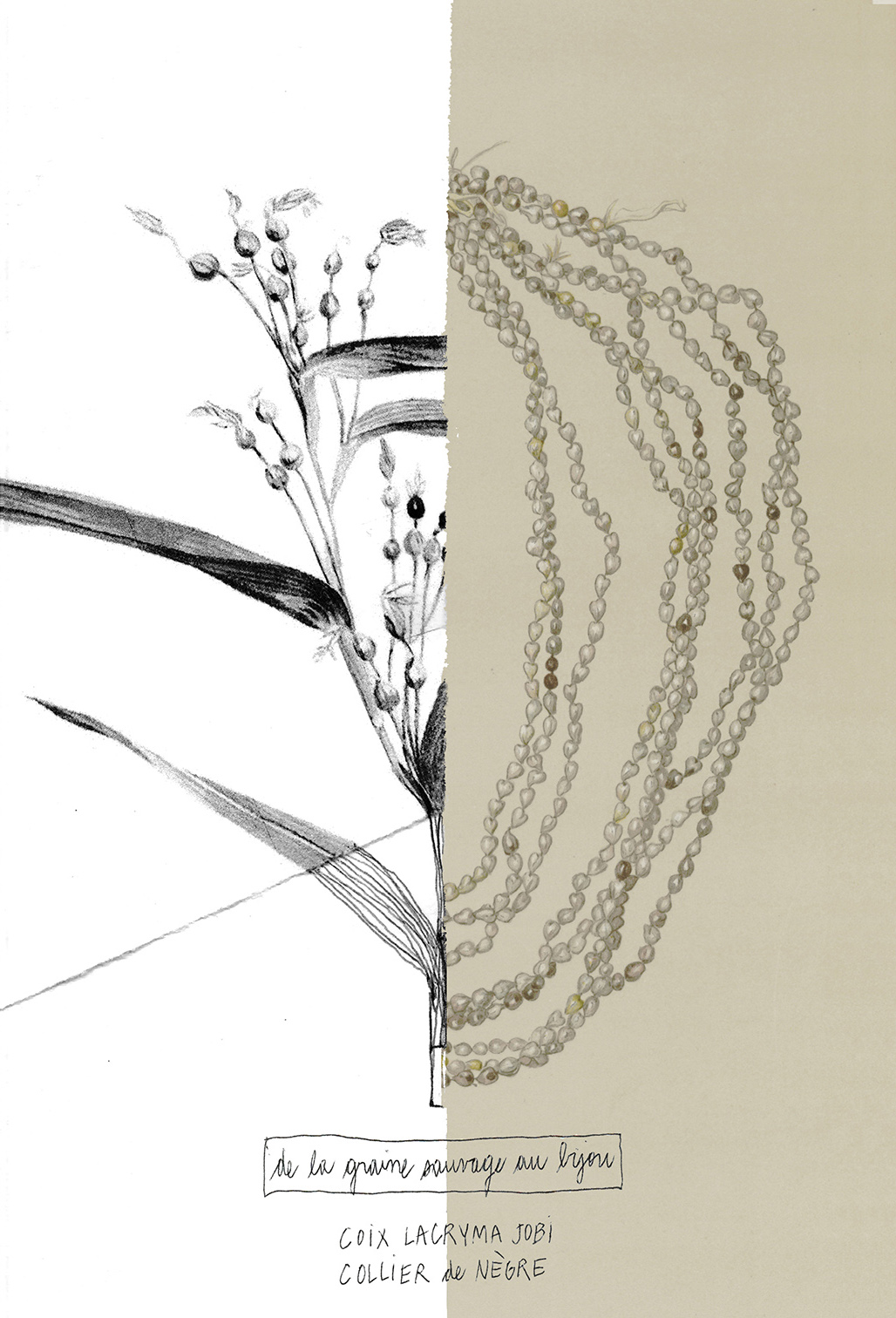

The grenn a maléré or "green job"

a wild seed turned into jewellery

The grenn a maléré (Coix lacryma-jobi, in Latin; Job's-tears, in English) is a tall, perennial grass that grows in wet ditches or flooded areas. It is recognisable by its leaves - which are similar to those of sugarcane - and it forms a seed from which greenish flowers emerge in spikes. While the places where it grows are generally unattractive, its seed on the other hand arouses significant curiosity. Oval in shape, its colour varies from greenish to bluish grey and brown. When the styles of the flower are removed, what is left is a hard and shimmering pearl, whose colourful - almost iridescent - effects render it similar to the mother-of-pearl produced by oysters.

Naturally pierced on both sides, this seed-pearl suggests decorative and contemplative uses which did not go unnoticed among the slaves of Guadeloupe and Martinique, who seized its potential as a response to the restrictions the French imposed on them. From the 1720s, the colonial authority had, in fact, put in place sumptuary laws which defined a "stylistic" code for slaves. These could not wear certain fabrics - notably lace and silk - and gold jewellery, for instance, as such materials were social markers of colonial society; as symbols of wealth and power, they were the prerogative of the ruling class - the white masters.

The grenn a maléré or "green job"

a wild seed turned into jewellery

The grenn a maléré (Coix lacryma-jobi, in Latin; Job's-tears, in English) is a tall, perennial grass that grows in wet ditches or flooded areas. It is recognisable by its leaves - which are similar to those of sugarcane - and it forms a seed from which greenish flowers emerge in spikes. While the places where it grows are generally unattractive, its seed on the other hand arouses significant curiosity. Oval in shape, its colour varies from greenish to bluish grey and brown. When the styles of the flower are removed, what is left is a hard and shimmering pearl, whose colourful - almost iridescent - effects render it similar to the mother-of-pearl produced by oysters.

Naturally pierced on both sides, this seed-pearl suggests decorative and contemplative uses which did not go unnoticed among the slaves of Guadeloupe and Martinique, who seized its potential as a response to the restrictions the French imposed on them. From the 1720s, the colonial authority had, in fact, put in place sumptuary laws which defined a "stylistic" code for slaves. These could not wear certain fabrics - notably lace and silk - and gold jewellery, for instance, as such materials were social markers of colonial society; as symbols of wealth and power, they were the prerogative of the ruling class - the white masters.

By making ornaments from the seeds of Job's-tears - which can be easily slipped on a thread - the slaves perpetuated the ancient practice of making jewellery from plants. Necklaces, bracelets, and even rosaries became a means of overturning the established order. By wearing these adornments during weekend meetings between slaves, they (especially women) sought to represent themselves as equal to white people magnified by their costumes and jewels whose pearly colour was surprisingly similar to these wild seeds collected from ditches. These meetings, that the slaves approached as spaces of freedom, were also the opportunity to mock the white bourgeoisie and its attitude. Later on, because of their recurrent use by the poorest, carrying these seeds would become a sign of misery. This was probably a tentative of the white society to end the practice.

The bwa lélé, the coui and the balé zo

plants helping everyday life

Originally, the bwa-lélé (Quararibea turbinata, in Latin; swizzle stick tree, in English) is a shrub - max. 6 metres high - that can be found in meso-hydrophilic zones typical of the mountainous regions of Guadeloupe and Martinique. Although recognisable by its large leaves - which can be up to 12 cm wide and that make the sound of crumpled plastic tablecloths when you compress them between your fingers - its picking remains a well-kept secret to this day. The "multi-level" architecture of the plant appears as a gift from nature: five horizontal branches start from the intersections on the main axis - the trunk - creating a propeller-like shape; each one of these intersections reproduces the same architectural principle. By cutting one of these joints and keeping part of the trunk stripped of its bark, you can obtain a bwa-lélé, a small forked stick that is used to stir drinks. According to the locals, this tool was inherited from the Karayib peoples during the short period of cohabitation between them and the first slaves; just like its cutting ritual which must correspond to a specific phase of the moon so that the shrub can continuously reproduce new growth. Today, the bwa-lélé is considered a traditional instrument of Creole cuisine and is associated with the preparation of the typical ti-punch cocktail and local soups like the migan.

The bwa lélé, the coui and the balé zo

plants helping everyday life

Originally, the bwa-lélé (Quararibea turbinata, in Latin; swizzle stick tree, in English) is a shrub - max. 6 metres high - that can be found in meso-hydrophilic zones typical of the mountainous regions of Guadeloupe and Martinique. Although recognisable by its large leaves - which can be up to 12 cm wide and that make the sound of crumpled plastic tablecloths when you compress them between your fingers - its picking remains a well-kept secret to this day. The "multi-level" architecture of the plant appears as a gift from nature: five horizontal branches start from the intersections on the main axis - the trunk - creating a propeller-like shape; each one of these intersections reproduces the same architectural principle. By cutting one of these joints and keeping part of the trunk stripped of its bark, you can obtain a bwa-lélé, a small forked stick that is used to stir drinks. According to the locals, this tool was inherited from the Karayib peoples during the short period of cohabitation between them and the first slaves; just like its cutting ritual which must correspond to a specific phase of the moon so that the shrub can continuously reproduce new growth. Today, the bwa-lélé is considered a traditional instrument of Creole cuisine and is associated with the preparation of the typical ti-punch cocktail and local soups like the migan.

Other objects, inherited from the same period, testify of original forms of "everyday invention". The coui, for instance, are containers - whose size can vary from that of a tablespoon to that of a vessel - obtained from the calabash tree. The fruits of the plant, the calabashes, are sorts of shells. Emptied of their content - which is highly poisonous for humans - they are cut in half, washed and dried in the sun. Lightweight, waterproof, relatively resistant and easy to manufacture, coui have always been a practical answer to the need for easy transport and content transfers, becoming 'super-normal' objects essential for life.

Similarly, the balé zo - a type of brooms - are produced quickly and simply from flexible and sturdy shrub stems - that serve as handles - and leaves selected according to the vegetation available in the area. Entirely plant-based, the balé zo were used to clean the immediate surroundings of the cases à nègre (the name for the buildings in which slaves used to live in Guadeloupe and Martinique) and later on to polish drainage channels. Like the bwa-lélé and the coui, the balé zo are among the testimonies of the ingenuity that originated in the frame of the sugarcane plantations and the search for a better quality of life.

Similarly, the balé zo - a type of brooms - are produced quickly and simply from flexible and sturdy shrub stems - that serve as handles - and leaves selected according to the vegetation available in the area. Entirely plant-based, the balé zo were used to clean the immediate surroundings of the cases à nègre (the name for the buildings in which slaves used to live in Guadeloupe and Martinique) and later on to polish drainage channels. Like the bwa-lélé and the coui, the balé zo are among the testimonies of the ingenuity that originated in the frame of the sugarcane plantations and the search for a better quality of life.

Bibliography

Servane Chauchix & Hector Poullet, Graines des Antilles, PLB Éditions, 2004

Séverine Laborie, « La représentation d'une société coloniale complexe », Histoire par l'image, accessed on June 4th, 2020

dach&zephir, “Palé an ka koutéw” - collection of vocal histories about creole culture, 2015 – ongoing research

About the authors

Graduates of the National School of Decorative Arts of Paris, Dimitri Zephir and Florian Dach founded dach&zephir in 2016. Mixing fervour and poetry, their projects echo the thinking of Martinican poet Édouard Glissant and celebrate the urgent and necessary diversity of the world. dachzephir.com / @dach.zephir / @eloj.kreyol